The territory known for more than two centuries as Acadia, included Canada’s Atlantic coast and corresponded approximately to the three present-day provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island.

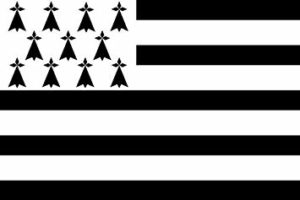

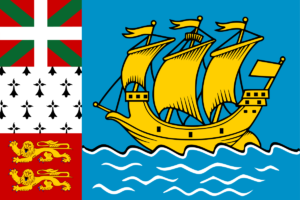

These coasts were frequented very early by Basques, whalers, and Breton and Norman cod fishermen, as the flag of Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon still reminds us today.

The name Acadia was first used in 1524 by an Italian, Giovanni de Verrazzano, who explored the North American coast (from the Hudson estuary to Newfoundland). He is so impressed by the beauty of the landscape and the lush vegetation that he calls the place “Arcadia”, in memory of a magical earthly paradise whose sweetness of life was so celebrated by the poets of ancient Greece. Spelled later without the letter “r”, the name will designate the Maritimes Region. Some establish its source among the Amerindians met by Verrazzano, who repeated a word whose consonance was quoddy, or Akade, or cadie, which means “a place”. It could also be the expression of the Micmac a-kaa-dik Indians, meaning “place where we are”.

The first sustainable settlement in Acadia dates back to 1604. Pierre du Gua, Sieur de Monts, obtained a trade monopoly and founded a first post on Île Sainte-Croix. After a disastrous winter, he transported this colony to Port-Royal. In 1613, the Jesuits founded a rival colony in Saint-Sauveur. But England and France claimed the same territory, and a Virginian privateer, Samuel Argall, destroyed the two French posts. In 1628, a Scottish colony was established in Port-Royal, and the country was named Nova Scotia. The territory passed successively, and on several occasions, under French and then English domination.

When Acadia was returned to France in 1670, the colony was revived. Colbert sent several contingents of soldiers and settlers there. But this boom did not last long. The governors of Acadia remained subject to those of Canada, and the St. Lawrence River increasingly attracted the city’s attention. Acadia was developing only slowly, by its own efforts. In conflict with religious authorities, Intendant Talon was recalled to France. He was replaced by Count Louis de Frontenac, who became Governor General of Acadia from 1672 to 1682 and then from 1689 to 1698. In 1682, encouraged by the Governor of Frontenac, Robert Cavelier de La Salle, descended the Mississippi (originally called the Mescacébé by the Indians) to the Gulf of Mexico and took possession of Louisiana, which was founded on 24 April 1699 by Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville. Unfortunately, because of its strategic location and the fishing grounds along its coasts, it was constantly the object of American envy. From 1654 to 1710, Port-Royal was besieged six times. The last attack, that of Nicholson in 1710, led to the surrender of all of Acadia to England by the Treaty of Utrecht (1713).

Nevertheless, the situation remained tense between Canada and the English colonies, as well as between the two metropolitan areas. The War of the Austrian Succession (1744-1748) had revealed Nova Scotia’s vulnerability, and the English authorities decided to effectively occupy the province by setting up English settlers and founding Halifax (1749).

The presence of the Acadians posed a delicate problem: they occupied the best lands and, in the event of war, their French sympathies would create a danger. Several times, there had been talk of deporting them, but London had refused, for reasons of expediency, to approve this draconian measure. The imminence of a new war silenced these scruples.

THE “GREAT DISTURBANCE”

In 1755, the decision was made to deport them en masse. The Great Disruption is underway. The Acadians, with the help of the Amerindians, tried to resist, but their forces being far too weak, they could not avoid tragedy, so they were loaded on ships and dispersed in the American colonies. They did not welcome these undesirables very well. Where they were able to land, the Acadians lived as outcasts in the midst of a hostile population. Those who had escaped spent several years in the woods and along the coast, hunted like wild animals and decimated by poverty and disease.

In 1755, the decision was made to deport them en masse. The Great Disruption is underway. The Acadians, with the help of the Amerindians, tried to resist, but their forces being far too weak, they could not avoid tragedy, so they were loaded on ships and dispersed in the American colonies. They did not welcome these undesirables very well. Where they were able to land, the Acadians lived as outcasts in the midst of a hostile population. Those who had escaped spent several years in the woods and along the coast, hunted like wild animals and decimated by poverty and disease.

Most eventually made their submission and were imprisoned in Halifax and Beauséjour. About 3,000 former settlers or refugees were captured on Île Saint-Jean after the capture of Louisbourg and shipped to England. It is estimated that, out of a population of some 15,000 inhabitants, 6,000 to 7,000 people had been dispersed in the American colonies, 3,000 had been transported to England and then to France, and more than 1,500 had died of drowning at sea, starvation or disease. About 1,500 had managed to escape to Quebec City and Chaleur Bay, and approximately 1,000 stray or prisoners remained in Nova Scotia.

After the Treaty of Paris (1763), hostility persisted for a few more years, then gave way to more liberal measures. Those who had remained were able to obtain land; the exiles were able to return home; several groups returned from Quebec City and Miquelon; entire caravans walked the New England road to Canada. They settled in Cape Breton, St. Mary’s Bay, Memramcook and Caraquet areas.

For many years, Acadians lived in darkness and isolation, often exploited, without schools, supported only by the presence of a few missionaries. However, their number was increasing rapidly. They eventually exercised some influence and obtained representatives in the legislatures. In 1854, Father Lafrance founded the Memramcook Academy, which later became a college and university. Other colleges were established in Bathurst, Church Point and then Edmundston. From these institutions would come out an educated elite, a clergy and professionals.

Gradually and smoothly, the Acadians managed to regain a place in their former homeland. Almost all of them Catholics and Francophones, they are fairly resistant to assimilation in New Brunswick, where they form a compact block. In 1766, 216 Acadians from Nova Scotia arrived in Louisiana (French colony ceded to Spain in 1762) where Acadians from Maryland were also welcomed in 1767. In 1766, about 90 exiles from Massachusetts went to Quebec City.

Those who are relegated to Europe face the same fate. Those that Virginia had rejected in 1755 were decimated by an epidemic of smallpox. Upon their liberation, the majority of the survivors crossed the Channel to France, where thousands of deportees were already dispersed in the Atlantic coast ports, from Boulogne to Bordeaux, via Saint-Malo, Nantes or La Rochelle.

The State paid them a pension, and for about twenty years tried to relocate them to French Guiana, the Falklands, Santo Domingo, Belle-Île-en-Mer or Corsica without much success. Acadians emigrated to the islands of Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, and in 1774 others agreed to become employees of fish merchants on the island of Jersey, settled in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

The largest wave of immigration took place in 1785 to Louisiana, where Spain, anxious to strengthen its position, brought back 1600 Acadians.

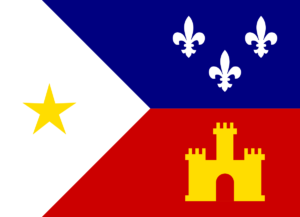

At the next convention, on August 15, 1884, in Miscouche, Prince Edward Island, the Acadians created their rallying sign: a flag, the three-coloured starred flag, and an anthem, Ave Marie Stella. Submitted to the convention by Father Marcel-François Richard, the flag is similar to that of France, whose tricolour blue-white-red base it has kept in tribute to the original land of the founding fathers, but is distinguished by the star that strikes its blue part.

The star

The star

Symbolic of the Virgin Mary, glorified in the Acadian anthem, this star, stella-maris – starfish – is also the one that guides the Acadian people through the trials and tribulations, just like the sailors passing through storms and reefs. To highlight the role of the Roman Catholic Church in the history of Acadia, she wears the papal colour, gold.

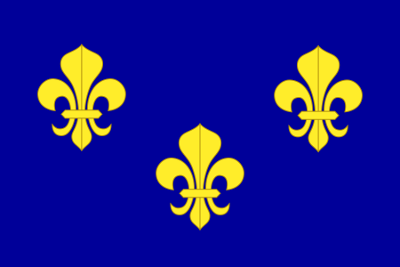

In 1955, Acadia immersed itself in remembrance, and, celebrating the bicentenary of the Great Upheaval, commemorated the suffering suffered two hundred years earlier: by reminding the world of the martyrdom of their ancestors, Acadians wanted to demonstrate that they would never forget. The Acadians of Louisiana (ACADIANA) created their Acadian flag that year, featuring the fort of the first French settlers and the fleurs-de-lis of Louis IV, from which the name Louisiana is derived.